People & Places

- The War of the Worlds is narrated in the first person

- The narrator gives an eyewitness account of his experience.

- He also reports events witnessed by others, including his brother (e.g. London chapters in Book One.)

- Most of the characters are unnamed and many appear briefly.

- Some named characters in Book One are killed off in IV/V/VI

Characters

The Narrator- Age early 30s

- Character: Intelligent, calm. Often expresses fear and even panic but always thinks logically.

- Like Wells author has some science training and lives in Woking.

- Narrator’s views broadly reflect those of Wells at that time.

- Wells/Narrator prone to class snobbery e.g. ‘Few of the common people in England had anything but the vaguest astronomical ideas in those days.’

- The Narrator’s wife (unnamed

- Seen entirely from narrator’s perspective but does offer a different angle on events.

- More nervous than the narrator but senses danger more clearly.

- Disappears for a large section of the novel but finding her remains the narrator’s quest

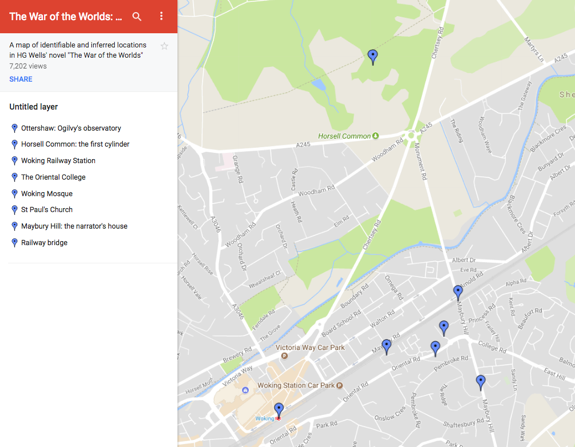

Professor Ogilvy

- Astronomer and one of the first people to observe a Martian

- Tries a peaceful negotiation with invaders no spoilers but does not end well!

Henderson (journalist)

- Joins Ogilvy to return to the pit

- In ‘white flag’ delegation to negotiate with the Martians, along with Stent (Chief Scientist) - see above!

The Curate

- A priest whose faith has been shaken by the Martians.

- Contrasts with narrator’s practical approach.

- Loses his sanity endangering the Narrator

The Artilleryman

- Soldier and fellow refugee

- Enters narrator’s garden in Book One

- The two men initially travel together

- Reunited in Book Two but character but now has romantic notions of rebuilding humanity.

- Ultimately the Artilleryman revealed as a fantasist.

Other characters are unnamed and/or only feature in individual episodes

Tweet Follow @eslreading Follow on Facebook

Locations

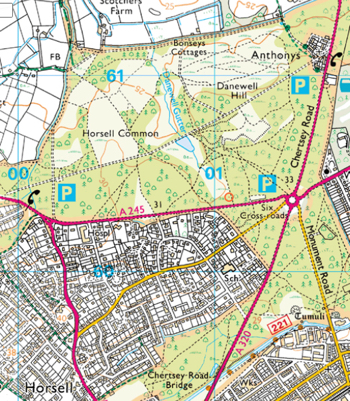

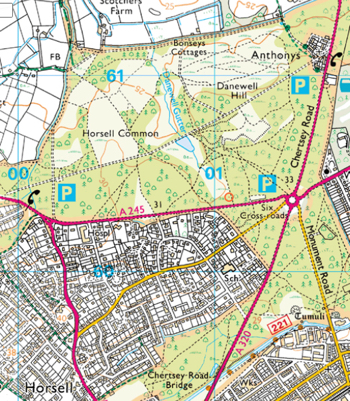

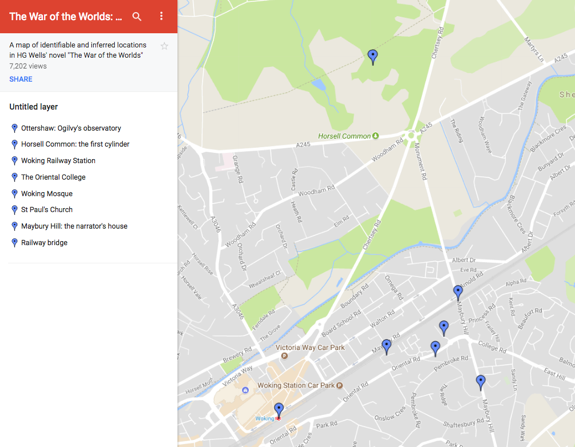

The story takes place in real places that are still there today. Horsell Common remains an area of ‘common’ (public) land.

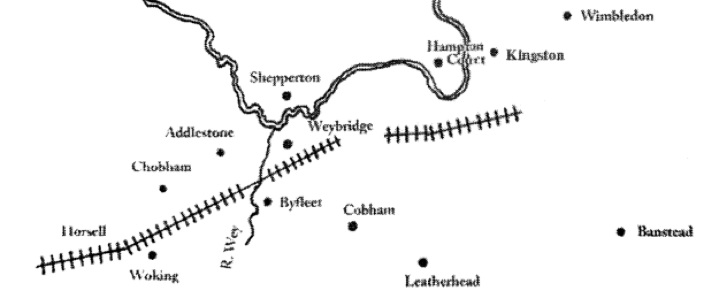

Woking was and is an affluent suburb to the south west of London. The Capital is easily reached by train and so it is popular with commuters (like Henderson the journalist, for example).

The railway line takes you to Waterloo Station - where the narrator’s brother twice attempts to get a train to Woking (on the Saturday and Sunday).

All the places mentioned are real locations, familiar to the author who lived on Maybury Hill. The early action all takes place in Surrey, a very prosperous county (then and now) that includes suburbs of London (like Richmond and Twickenham).

The narrator also lives on Maybury Hill When the fighting starts, he takes his wife to Leatherhead (about eleven miles away).

London

London is the most important city in the world at this time, though increasingly challenged by New York. Much critical attention has been given to the symbolism of the imperial capital - falling to the ‘alien’ forces. Wells alludes to this analogy but the link with colonialism can be overplayed.

The War of the Words is first and foremost a gripping adventure story.

Horsell Common

The story takes place in real places that are still there today. Horsell Common remains an area of ‘common’ (public) land.

Woking was and is an affluent suburb to the south west of London. The Capital is easily reached by train and so it is popular with commuters (like Henderson the journalist, for example).

The railway line takes you to Waterloo Station - where the narrator’s brother twice attempts to get a train to Woking (on the Saturday and Sunday).

All the places mentioned are real locations, familiar to the author who lived on Maybury Hill. The early action all takes place in Surrey, a very prosperous county (then and now) that includes suburbs of London (like Richmond and Twickenham).

The narrator also lives on Maybury Hill When the fighting starts, he takes his wife to Leatherhead (about eleven miles away).

London

London is the most important city in the world at this time, though increasingly challenged by New York. Much critical attention has been given to the symbolism of the imperial capital - falling to the ‘alien’ forces. Wells alludes to this analogy but the link with colonialism can be overplayed.

The War of the Words is first and foremost a gripping adventure story.

Horsell Common